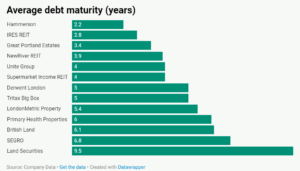

Those with shorter debt maturities face significant refinancing risks, while those with longer profiles are better positioned to ride out the storm.

European real estate investment markets have experienced significant shifts in the underlying drivers in recent years. Mostly this has been driven by macroeconomic conditions, including rising interest rates as a response to spiking inflation, and a general economic malaise that has permeated most markets, though less so Ireland.

This has dented confidence to levels not seen since 2011 or 2012, with the lack of available financing, at sensible pricing levels, one of the primary issues. An oddity that has emerged in this cycle is that market rents have continued to climb, even for offices, while investor confidence remains on the floor. The turnaround, which is edging closer and closer, will be driven by debt, not by occupier demand.

As central banks tightened monetary policy to combat inflation, listed property companies (mostly REITs) and other property funds faced growing questions related to their indebtedness. Much of this was debated around Boardroom tables, with many conversations drifting to AGMs as investors began to air frustrations.

Key concerns included soaring loan-to-value (LTV) ratios as property values fell, a situation outside the control of management, but it was how executives reacted to rising debt costs which became the key battleground.

As debt began to edge towards maturity, the rising cost of refinancing became an issue that could push management teams to make hasty, and even rash decisions on what to do with their portfolios. Publicly listed property companies, with regular reporting lines, became a critical lens through which broader investors were able examine these challenges, as they offer transparency into debt levels and refinancing risks. In reality, it was these public companies that were much more cautious on debt than in previous cycles than in private markets, and now present the best re-rating opportunities.

Loan-to-value is a key metric used to measure the extent of indebtedness in real estate. It represents the proportion of a property’s value that is financed through debt. In a rising interest rate environment, high LTV ratios increase risk as property values fluctuate and borrowing costs increase.

Many firms with high LTVs faced considerable pressure from investors, and too many were seen as companies to avoid in an uncertain financing market. Though, now in a falling rate environment, these are likely to be companies that will screen well with investor analysts as an opportunity to bounce back.

Another crucial factor when assessing the indebtedness of real estate investors is the maturity profile of their debt. The timing of refinancing and the prevailing interest rate environment at the time of maturity can have a significant impact on financial stability.

The timing of debt maturities is crucial in today’s environment. Those with shorter debt maturities face significant refinancing risks, while those with longer profiles are better positioned to ride out the storm. None will want to be in a position whereby they have to refinance over the next 12 months.

The last two years have seen the real estate market face sharp increases in borrowing costs. For much of the last decade, low-interest rates allowed real estate investors to finance acquisitions and development at historically low costs. However, with central banks raising rates aggressively to combat inflation, the cost of capital has surged.

In the UK, refinancing rates for commercial real estate debt have risen to between 5 per cent and 6 per cent, up from lows of 2 per cent to 3 per cent in 2021. This is significantly squeezing margins for REITs, particularly those with higher leverage and shorter debt maturities.

Those who locked in rates early saw stability in costs, but the market did not necessarily reward them. Supermarket Income REIT being a case in point.

Others benefitted from longer debt maturity ratios, like Hammerson, who have ridden the re-pricing wave, and now have refinanced at an advantageous time in the market.

In Ireland, refinancing costs are similarly elevated. The European Central Bank’s (ECB) rate hikes have pushed borrowing costs to around 4 per cent to 5 per cent, creating challenges for highly leveraged companies, where debt service costs rose dramatically through 2023 and 2024, resulting in a weakening earnings performance for shareholders. IRES REIT suffered from this, it is likely that Green REIT and Hibernia REIT would have been in a similar situation had they still been around.

In the broader European markets, refinancing rates for investment-grade real estate have risen to between 3.5 per cent and 4.5 per cent. Companies like Segro, with lower leverage and long-dated debt, have managed to secure financing at the lower end of this range. However, companies like Hammerson, facing sector-specific challenges and higher leverage, are likely to pay a premium for refinancing. Though with the Dundrum debt now refinanced, this is likely to considerably strengthen Hammerson’s hand.

The Bank of England’s base rate now cut to 5 per cent, the SONIA rate (a key benchmark), which now hovers around 5.0 per cent-5.2 per cent.

This has directly driven borrowing costs. Current margins over SONIA (typically between 1.25 per cent -2.5 per cent) depend on the property companies credit profile, the type of financing (e.g., green bonds, revolving credit), and the maturity.

High-quality REITs with solid credit ratings (e.g., SEGRO, Tritax) are still able to secure relatively favourable rates, while riskier players face higher margins.

As a result, many real estate firms are currently paying 6.5 per cent – 7.5 per cent or higher for newly refinanced debt, compared to much lower rates of 2 per cent – per cent in previous years. Much of this impact has still to be felt on company results. 2026 is a key re-financing year for many, so where rates sit then will be critical.

Listed real estate companies offer a microcosm of the broader market dynamics, with loan-to-value ratios and debt maturities being key indicators of their vulnerability. In a tightening capital environment, those with lower leverage, longer debt maturities, and exposure to growth sectors like industrial real estate, such as Segro, were best positioned to navigate the storm, the opposite is increasingly true in a period of loosening credit conditions.

Given how cheap many of the more indebted companies trade, 2025 may be their year to re-rate, provided they hold on until then.