The government’s proposal to ban upward-only rent review (UORR) clauses under the Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill has reignited an old but largely settled debate. While positioned as a measure to protect small retailers and rebalance landlord-tenant power, the proposal is ill-timed, economically misdirected, and legally questionable. It risks disrupting a market that has already evolved beyond the rigidities it seeks to eliminate.

Upward-only rent reviews have long been controversial, but the reality in 2025 is not the same as it was in the early 2000s. The leasing market has moved on. This intervention seems less a response to a pressing problem than a populist misfire aimed at perceived injustice rather than real economic priorities.

The Market Has Already Moved On

Today, most new leases are short, flexible, and increasingly tailored to the needs of individual occupiers. Lease lengths of under five years are now common across all sectors. Turnover-based rent models, index-linked mechanisms, and break clauses are standard in new lettings. Even in prime office locations, long leases are the exception rather than the norm.

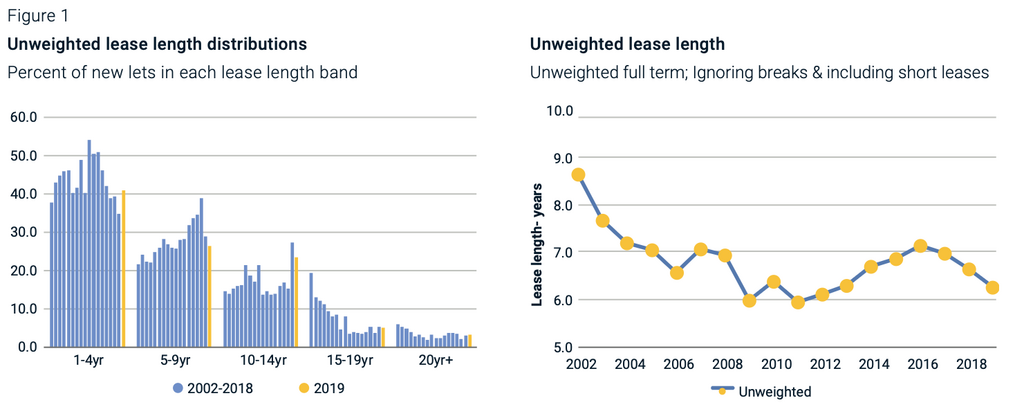

This trend is not speculative. The 2019 Lease Events Review, a joint study by MSCI and the British Property Federation, confirms a dramatic shift in leasing practices. According to the report, the average length of new leases signed in 2018 was just 5.7 years, with a median of only 3 years. A full 76% of new leases were under five years. Furthermore, nearly 60% of leases included break clauses, empowering tenants to reassess their property strategy partway through a term.

Such findings reflect structural changes rather than cyclical anomalies. Flexibility has become the currency of occupier demand. Businesses, particularly SMEs and digitally-enabled service operators, now require adaptability in real estate commitments to match fluid staffing, agile work models, and unpredictable consumer demand. The property industry has responded accordingly. That responsiveness renders regulatory intervention unnecessary and potentially counterproductive.

Misdiagnosing the High Street’s Ills

The government’s narrative positions UORRs as a central culprit in the decline of the High Street. That diagnosis is shallow. Business rates remain the most significant financial pressure on small and independent retailers, outstripping rent concerns by some distance. Rising operational costs, structural changes in consumer behaviour, and shifts in urban land use have all reshaped the economics of retail far more profoundly than any clause in a lease.

Eliminating UORRs will not revive town centres. In fact, it may deter investment in marginal locations where income predictability still supports funding and redevelopment. The better response would be a comprehensive reform of business rates, combined with targeted regeneration and planning flexibility. Lease terms, by contrast, have already adjusted to the realities of a different retail world.

Legal Certainty Still Matters

One of the principal strengths of the UK commercial property market is the clarity and enforceability of its legal framework. For decades, that stability has attracted capital from global pension funds, insurers, sovereign wealth funds, and long-term real estate vehicles. While UORRs are no longer standard, their presence in some asset classes continues to support income visibility and debt security, particularly in sectors requiring high upfront capital expenditure.

To remove that option altogether is to narrow the field of acceptable investment formats without evidence that doing so would materially help occupiers. At worst, it creates ambiguity around income expectations, undermines valuation consistency, and complicates loan covenants. This is a time when the government is urging pension funds to allocate more capital into real assets. Removing contractual tools that support that ambition sends an incoherent signal.

Let the Market Continue to Evolve

Reform should encourage transparency and optionality rather than impose rigid limitations. The industry has already created modern leasing codes, and many landlords now adopt practices well beyond those codes as a matter of course. Indexation has replaced fixed reviews in many sectors. Co-working and meanwhile-use arrangements are expanding in offices and urban retail. Turnover rents are embedded in leisure and outlet leasing models. All of this has occurred without legislative force.

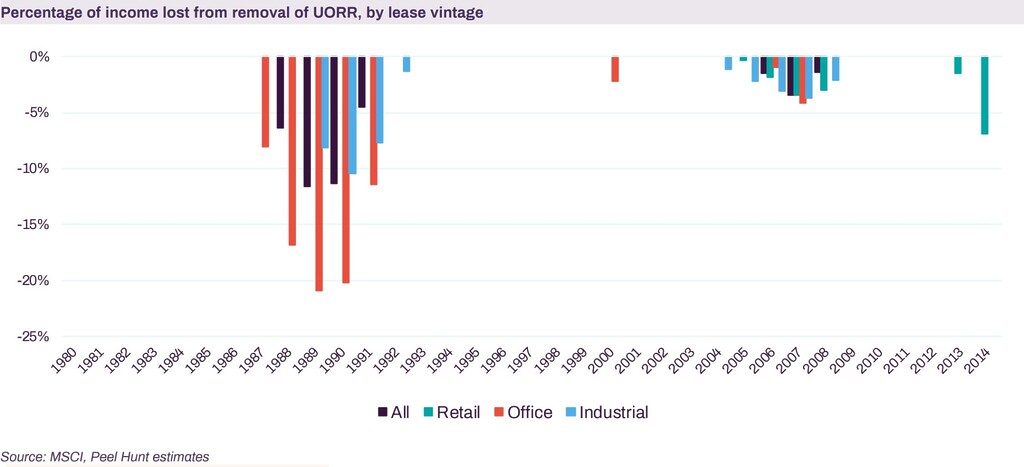

Blanket abolition of UORRs risks freezing a market that is already adapting. Worse, it implies distrust in the negotiating capabilities of tenants and landlords alike. Where two parties reach an agreement that suits both their needs, the law should not intervene without compelling justification. That justification is absent here. In fact, analysis by Peel Hunt shows that just a fifth of ten-year leases over the past 45 years would have been impacted by UORRs, with an average loss of less than 6%. That is hardly the basis for sweeping legislative interference.

Reform Through Engagement, Not Edict

If the government believes there is a market failure in lease structuring, it should start by convening stakeholders. That includes tenants, landlords, investors, valuers, lenders, and professional bodies. It should assess whether there are gaps in data, understanding, or incentives that merit policy attention. But to legislate first and consult later reverses the proper order of policymaking.

Voluntary adoption of lease models that offer predictability and flexibility can be encouraged through data-sharing, benchmarking, and public procurement standards. Investment into secondary towns can be supported through tax policy, infrastructure, and zoning reform. None of these depend on scrapping UORRs by statute.

Conclusion: Maturity Over Mandate

This proposal is not a necessary or timely reform. It is an overreaction to a perceived injustice that no longer reflects market practice. Lease reform should be evolutionary, not prescriptive. It should empower negotiation, not constrain it. And it should proceed with the same commercial maturity that tenants and landlords already demonstrate every day.

The government has other tools at its disposal to support the High Street, attract capital, and modernise retail property. Discarding a lease mechanism that is already in decline, but still useful in specific contexts, is not one of them. Reform should be proportional, consultative, and grounded in the economic realities of 2025, not the political rhetoric of 2005.

—

To explore these issues in greater depth, Lauder Teacher recently hosted an expert call featuring Liz Peace CBE and Andy Martin, where they shared their perspectives on the proposed reforms, historical context, and the practical realities of the UK leasing market.

A recording of the session is available to view on our website: See below or a direct link to Watch here.